FREE Download: Exercises in Meter 4/4

FREE Download: Exercises in Meter 7/8

Gregory Kustka-Tsimbidis is a drummer and composer hailing from Toronto, Ontario. Greg holds a Bachelor’s of Music in Jazz Performance from McGill University. He currently resides in Montreal, where he works as a freelance drummer, composer, and educator.

What is meter?

At the most fundamental level, meters (or time signatures) are tools used by musicians to quantify the division and progression of time within a musical piece. In western musical notation, meters are expressed as two numbers stacked upon one another. The most common example of this is 4/4 . In this notation convention the bottom number is used to denote a subdivision, and the top number is used to denote the occurrences of that subdivision within a given bar of time. So, in the case of the aforementioned 4/4 , a bar of time is equal to four quarter notes (A bar of 7/2 translates to seven half notes, a bar of 9/8 translates to nine eighth notes, and a bar of 13/16 translates to thirteen sixteenth notes). I am sure that many a student reading this post will be familiar with this definition of meter. However, regardless of one’s level, a reminder of the fundamental mathematical relationship between meters is useful, as it provides an important insight: the processes used to create any given meter are the same, and so it follows that one set of processes can be utilized in the pursuit of learning any given meter. Of course, one is required to invest a wealth of time into each separate meter of interest, as differences in temporal space, subdivisions/groupings, and appropriate phrasing all provide unique challenges for each meter. However, just as different meters can be understood via the lens of their shared framework, the differing demands of playing each of these meters can be approached utilizing a single framework of exercises, which may be applied across all meters. Through the remainder of this article I will break down a series of such exercises, with the goal of providing a pathway from complete beginner to fluency in any meter.

Why play different meters/ The importance of listening

Before proceeding any further, I believe there is an important question that needs to be addressed: What is the point of different meters? While the answer to this may seem obvious to some, to the reader wholly new to music, or new to “odd” meters, the sterile mathematical definition provided above fails to express the musical affect achieved by utilizing various meters. At the end of the day, it is the emotional and expressive qualities of music that speak to us. Meters are to rhythm what key signatures/modes are to harmony. There are unique characteristics to each that have a drastic impact on the resulting sound of any given piece of music. The best way to discover what these qualities are is to listen to music in the meter that interests you. This again may seem pretty obvious, but I have encountered more than one student who expressed an interest in learning a new meter, only to then inform me that they don’t actually listen to any music that utilizes that meter. This does not work. It’s like trying to learn a new style of music without actually knowing what it sounds like. This emphasis on listening is paramount, and is perhaps the most important factor in learning new meters. Most beginner students I have encountered have a basic conception of what 4/4 feels like, but are completely at a loss with something like 9/8 . This is not because 9/8 is inherently more difficult than 4/4 , but rather because the vast majority of western music is in 4/4. Familiarity breeds understanding. This is the key to any and all meters. So, before investing the hours of practice required to learn a new meter, ask yourself “what is it that I wish to express?” and “how will practicing this meter help me to achieve that?” Put the music first. Use math and counting as a tool, but also focus on the sound of what you are playing. What makes 5/4 feel different than 4/4? What makes it sound different? Keep this focus in your practice, and eventually you will reach a point where you can truly hear phrases and music that are in various meters. It is this point that marks the difference between someone who truly makes music utilizing various meters, and someone who uses them just because they can.

Exercises

With all of that taken care of, let’s get into the exercises. I have chosen to discuss a series of exercises that I believe are fundamental in addressing the various factors that inform a drummer’s efficacy in a given meter. All of these exercises are useful, but they do not represent all of the useful exercises one could practice to develop mastery of a new meter. I would need a near never-ending blog post for that. However, there is a simple truth I alluded to above that can allow any student to develop their own regimen for practicing meter: Any exercise can be adapted and applied to any meter. If you truly want to get good at 7/4 , just practice everything in 7/4. Rudiments, grooves, fills, etc. Just adapt any exercises you already do to this new framework. For some though, this is easier said than done, and it can be tough to decide what is most valuable to spend one’s time on. It is for this purpose that I have created this article; as a jumping-off point for your own explorations. I want these exercises to be useful to drummers of any level, so to that end I will provide examples of each exercise applied to both 4/4 and 7/8. Every exercise will be explained in a general way that can be applied to any meter of interest, with the sample meters demonstrating said application at different levels of difficulty and commonality. For each exercise I will discuss, there is a corresponding notated example available as a PDF to download at your leisure. Let’s get into it!

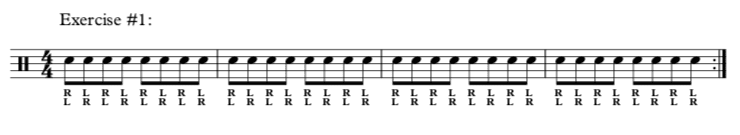

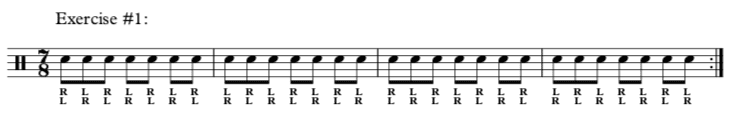

Exercise #1:

The first exercise is very simple. All it entails is a single stroke roll on the snare drum. The key is that this roll will be played over top of any meter your wish to learn. Create a playlist of a few songs in the meter of interest, then play along with them, sticking to the simple single stroke roll for now. You can do this at various rates/subdivisions, depending on the speed of the song and what fits into the given meter. Switch between right hand and left hand lead. One song in 4/4 that I like to do this with is “Sex Machine” by James Brown. This song has a straight eighth funk feel, so I may choose to play the single stroke as quarter notes, eighth notes, or even sixteenth notes. One thing to note about this exercise is that the point is not to count. Counting is an important part of the process when learning a new meter, but so is developing a “feel” for the meter. For this exercise the focus is on listening intently to the music you are playing along to, and trying to lock in with it as much as possible. By applying a consistent and focused effort to this exercise, you will train both your mind and body to develop a feel for the temporal space that a given meter occupies, while also exposing yourself to phrasing idiomatic to that meter.

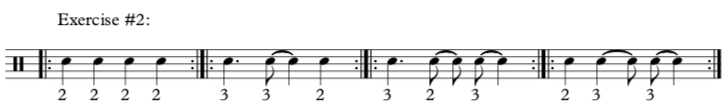

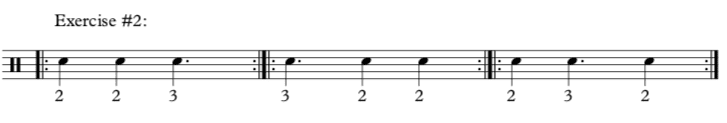

Exercise #2:

4/4

7/8

Exercise two is all about breaking meters down into manageable groupings, and using those groupings in the creation of ostinatos. Any meter we play can be broken down into groupings of two and three. This becomes incredibly useful, especially as we begin to explore larger meters. Breaking down a meter like 4/4 in this manner may not seem too important, as groupings of four are within our capacity to count and feel. 7/4 begins to be more challenging, and by the time we get to meters like 13/16, feeling the bar as a single chunk becomes almost impossible. Instead, we break each meter down into manageable chunks, using two’s and three’s as building blocks. There are many ways that one can break down a meter. See the attached PDF for a few examples using eighth notes as the base subdivision. Once you have a list of groupings in the meter you wish to learn, it’s time to start playing them.

Begin by counting out loud. Being able to count out loud rather than just in your head is key. It will help develop comfort and rhythmic independence in the given meter. Count based on the grouping you are playing. So, let’s say we want to play a 2-2-3 grouping in 7/8 . Rather than counting 1-2-3-4-5-6-7, we will count 1-2-1-2-1-2-3.

Once this feels comfortable, choose a limb/surface of the drum set and begin to play in unison with the “1” of each grouping. So, in the example of a 2-2-3 grouping in 7/8 , you will play two quarter notes and a dotter quarter note. This can and should be done with every limb, one at a time, and at a slow tempo. Do this exercise with each possible grouping in the meter you are trying to learn.

Tip: Once you are comfortable with every grouping that resolves each bar, begin to work on groupings based on larger subdivisions that resolve after multiple bars. A great example of this is playing quarter notes in 7/8. Because there is an uneven amount of eighth notes in a bar of 7/8, the quarter notes will not resolve after a bar. Rather, they will be displaced going into the next bar, and will resolve after two bars of 7/8 . This grouping corresponds to one bar of quarter notes in 7/4 . This is referred to as feeling the big pulse, and will help immensely with freeing up one’s phrasing.

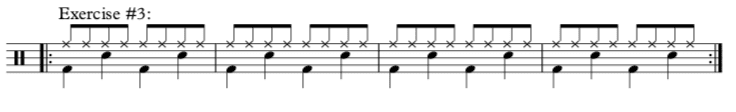

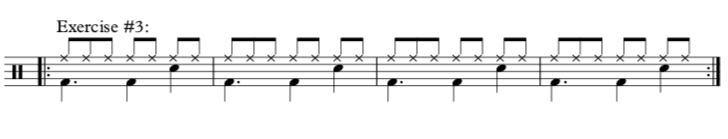

Exercise #3:

4/4

7/8

Exercise three is moving from playing a single rhythm to creating a groove in the relevant meter. If there is a particular song you would like to learn, this is a perfect time to start learning the main groove. Or come up with your own. Or do both. It doesn’t matter, just pick a groove that moves you, and play it A LOT. I suggest starting with something relatively simple. The examples I provide for this exercise are basically just fleshed out and orchestrated versions of exercise two. Start from this place, playing a variety of grooves that correspond to the different groupings you have worked on. As the basic technical execution of the groove begins to come together, start to focus on musical considerations such as dynamics, accent patterns, and pocket. Repetition is key in isolating and developing fine details.

Tip: Once you begin to feel comfortable with a given groove, start to intersperse bars of groove with bars of space. So, for example play three bars of a groove in 7/8 , then one bar of complete silence. Gradually increase the bars of silence. Utilize your metronome, and try to really lock in with the downbeat when you come back in. Practicing truly feeling a bar of 7/8 without having any physical crutch for keeping the time (try to avoid bouncing the hi-hat foot) will greatly improve your comfort and flow in that meter, and will also help to mitigate problems of overplaying. If you start from a place of playing nothing, and can make that space breath and stay in the pocket, then once you start to add notes into that space they will arise from a place of musical consideration, rather than time keeping necessity.

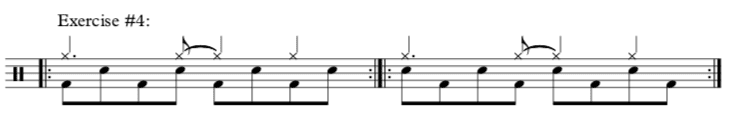

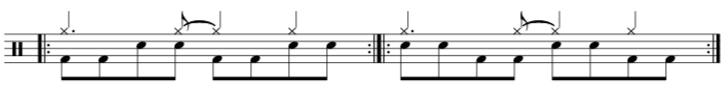

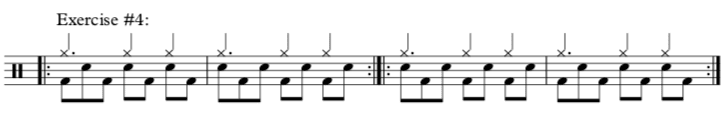

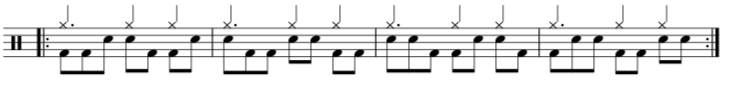

Exercise #4:

4/4

7/8

Exercise four is to address issues of co-ordination and independence. Like with the previous exercise, the basis for this exercise is the groupings of two’s and three’s that we worked on in exercise two. As I’m sure you can see by now, these grouping patterns are not simply a counting tool, but also translate into very practical and musical ostinatos and phrasing patterns.

In this exercise we will treat the grouping patterns like a clave. First, choose a limb to play the clave. In the case of the notated example, I have chosen the right hand on the ride cymbal (LH if you are left handed). This is good as a starting point. However, as you practice this exercise, you can try putting the clave elsewhere, such as in the left foot, or as a cross-stick.

The next step is to play through the first page of stick control, orchestrated between two of the other limbs, in whatever subdivision works for the meter you are playing. In the case of the provided examples I have chosen to use the bass drum and snare drum; again, a good starting point. In these examples, the bass drum corresponds to the RH of stick control, and the snare drum corresponds to the LH (the 4/4 example shows the first four lines of stick control played in this manner; the 7/8 example shows the first three).

As with the clave, you can expand this orchestration to other limbs as you gain fluency. The number of variations you can play is immense, if you consider all the possible groupings in a meter, as well as all the combinations of three limbs that can be used. Try not to let these possibilities overwhelm you though. Just pick combinations that interest you. You will see great benefits from any combination. This exercise is very challenging, so take it slow and try to really focus on each limb lining up where it’s supposed to.

Tip: You will notice in the 7/8 examples that the sticking patterns do not line up every bar. This will be the case even for a relatively simple meter like 3/4 , and is a great opportunity to practice over-the-barline phrasing. As you are practicing the exercise try to keep track of where the pattern resets. This will help both with developing phrasing, and with hearing multi-bar phrases, riffs, and forms.

Exercise #5:

The last exercise I will discuss is very similar to the first exercise. Choose a subdivision that fits in the meter you are working on, and just improvise in that subdivision, within the meter. For this exercise there are no specific sticking or orchestrations. In fact, there are no real guidelines besides sticking to the one subdivision. I am a real proponent of playing as a means to discover what you don’t know, and what you need to work on. The mistakes you will make while trying to improvise in this new meter will give you insights into cool phrases to work on, sticking patterns that fit (or don’t), and time and co-ordination issues that need to be worked on.

If you want to add a bit of structure to the exercise, try alternating between playing bars of a groove, and bars of improvising. Don’t be afraid to leave space. Try to practice counting out loud while improvising, utilizing different groupings. See how that changes your phrase ideas. Just play! There are plenty more technical exercises that you can and should work on, but I believe that regularly letting go of that stuff and just exploring the drums is a really important part of developing one’s musicality and sound, as well as fostering a fun and sustainable relationship to the instrument.

Gregory Kustka-Tsimbidis is a drummer and composer hailing from Toronto, Ontario. Greg holds a Bachelor’s of Music in Jazz Performance from McGill University. He currently resides in Montreal, where he works as a freelance drummer, composer, and educator.

It is appropriate time to make some plans for the longer term and it’s time to be happy. I have learn this publish and if I may just I want to recommend you some attention-grabbing issues or suggestions. Maybe you can write next articles relating to this article. I desire to read more things approximately it!